Questions about Oakland Promise: If it wasn’t a nonprofit, what was it? What happened to the money for scholarships for kids?

Sep 12, 2019

By Ken Epstein

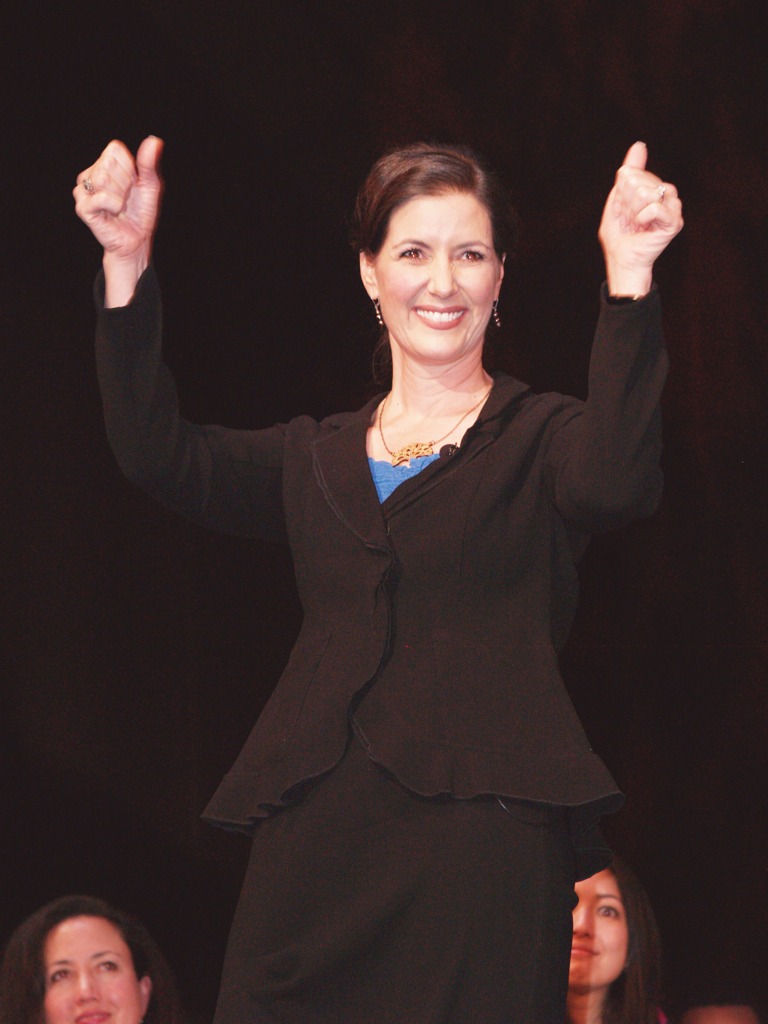

Questions continue to surface about the organization and accountability of “The Oakland Promise,” Mayor Libby Schaaf’s signature initiative that has raised millions of dollars since 2015 to help low-income families “to triple the number of high school graduates who …complete college by the year 2024.”

Though the Promise’s s lofty goal is widely popular among Oakland residents, that support has not silenced demands for full transparency about the legal status is of this organization, which has operated out of the Mayor’s Office, and how it is spending public money and resources.

Most significantly, Oakland Promise is wide perceived as a nonprofit organization. But that has not been the case, at least until recently.

The organization was not listed as one by Guidestar, a website designed to provide ”the highest-quality, most complete nonprofit information available.” Nor was Promise registered as a nonprofit with the State Attorney General.

According to an email to the Oakland Post on Aug. 29, 2018, Oakland Promise was described by its backers as a “public-private effort” backed by four organizations: the City of Oakland the Oakland Unified School District, the East Bay College Fund and the Oakland Public Education Fund.

Since July, however, Oakland Promise has become a nonprofit, merging with the East Bay College Fund and taking over its nonprofit status, according to the East Bay Times. Mialisa Bonta, president of the Alameda Unified School Board and wife of Assemblyman Rob Bonta, has become organization’s CEO, taking over the leadership from David Silver, who is a city staffer in the Mayor’s Office.

Another question is what has happened to the money that the city gave Oakland Promise to start set up college saving accounts for children. A copy of a Public Records Act request forwarded to the Post asked for information about the total of $1,150,000 that the city budgeted for Oakland Promise for these savings accounts. But according to the city’s Finance Department on Aug. 16, “The city has not yet made payments on behalf of Oakland Promise from funds earmarked for this program in the adopted budgets for 2016-17, 2017-18 (and) 2018-19. The requested documents (canceled checks) do not exist.”

Council President Rebecca Kaplan in an email explained why she has asked City Auditor Courtney Ruby to audit Oakland Promise.

“Many people have been asking the questions I sent to the auditor – and many members of the public, And even the League of Women Voters, have expressed concern about the Oakland Promise funds. It is perfectly reasonable for anyone to want to know where the money is. This is large amounts of tax-payer funds that were promised to be used to set up college savings accounts for each Oakland kid, as they enter kindergarten.”

“We want to know where the money is – and where the college savings accounts are – that were supposed to be set up each year, starting in 2015,” Kaplan said. “By now they should have grown a lot if they had been set up as promised and as funded in the city of Oakland budget, for the Kindergarten to College Program.”

Asked about Council President Rebecca Kaplan request for the City Auditor to conduct an audit of Oakland Promise, the Mayor’s Office replied, ““Kaplan wants Oakland taxpayers to fund her petty political vendetta masquerading as an audit. And tragically she’s targeting the Oakland Promise – a program started by the City of Oakland to send low-income kids to college with scholarships and mentors. She needs to immediately withdraw this taxpayer funded political score settling – because it hurts taxpayers and kids.”

| Responding, Kaplan said, “The Mayor’s Office says I’m asking for tax payer money, but that is flatly false. I am not requesting any money. I have asked our independently elected City Auditor for help getting information about where the college savings accounts they promised for Oakland youth are. The auditor is paid a regular salary.” |

The Alameda County League of women Voters(LWVO) expressed concerns about Oakland Promise when Mayor Schaaf and the Promise organization backed Measure AA last November, which would have created a $198 parcel tax to provide funding for Oakland Promise for 30 years. In its voters’ guide, the League took a neutral position, saying, “We found it unclear how moneys in the Oakland Promise Fund would be spent .”

Measure AA won more than 50 percent of the vote but failed to pass because it needed a two-thirds majority. That ruling is now being challenged in court, and according to observers, the case may take three years and end up at the state Supreme Court.

According to its website (Oaklandpromise.org), the organization consists of four programs:

- Brilliant Babies – “Through participating early childhood programs and pediatric clinics, parents are offered the opportunity to open a Brilliant Baby college savings account seeded with $500 as an early investment and source of inspiration for their baby’s bright future,” according to Oakland Promise;

- Kindergarten to College – “Open(s) an early college scholarship seeded with $100 for all Oakland public school kindergarten students;”

- Future Centers – creates college and career advising center on middle school and high school campuses, replacing services lost by the public schools as a result of cutbacks;

- College Scholarships and Completion – $1,000 annual scholarships to students going to community colleges and up to $4,000 a year for students attending four-year colleges.

Questions that remain to be answered are how many $500 accounts have been set up through Brilliant Babies; how many $100 scholarships have been established through Kindergarten to College; how many Future Centers have been set up and how many hours of support they have provided to students; and how many community college and four-year college scholarships have been awarded.

During the years that Oakland Promise was not a nonprofit, the Oakland Public Education Fund served as the organization’s fiscal sponsor and can share budgetary information, including IRS Form 990; audited financial statements; Form 1023 and all correspondence in relation to the production and completion of this document; and a IRS Determination Letter,” according to Maggie Croushore, director, development, of Oakland Promise.

By deadline, the Post had not received that data nor an answer questions about the cost that Public Education Fund charges to serve as Oakland Promise’s fiscal sponsor and numbers of students and families served by the programs.

Croushore told the Post that during the three years, 2015-16 to 2017-18, the Oakland Promise spent a total of $19.9 million or 94.7 percent of its budget on program costs ($11.3 million) and scholarships and saving accounts ($8.6 million). During that time, the initiative spent $1.1 million or 5.29 percent on administrative expenses. Total revenue during the three years was $33.5 million. However, now that the Oakland Promise has become a nonprofit, costs of administrative overhead could potentially increase if most the organization’s 47 employees are paid out of the budget instead of being provided without cost by the City, OUSD and other agencies.

In an email to the Post, Schaaf spokesperson Justin Berton said, “The nature of the Oakland Promise has always been a collaboration with OUSD and community partners to send underrepresented kids from Oakland to college with scholarships, mentors, and the life-skills to end patterns of generational poverty and institutionalized racism. Every Oaklander should be proud their City has come together to send more than 1,400 Oakland kids to college (and counting), seeded more than 500 ‘Brilliant Baby’ scholarships, and worked tirelessly to support Oakland families and their children from cradle-to-career.”