Two Developers in Running to Restore Historic Kaiser Convention Center

Jan 9, 2014

Posted in Economic Development, Responsive Government

By J. Douglas Allen-Taylor

The announcement of one of the most important Oakland public works restoration projects in recent memory went virtually unnoticed during the recent mayoral campaign.

Last September, the City of Oakland issued a Notice of Development Opportunity to restore the closed-down Kaiser Convention Center at the western end of Lake Merritt as a public-private partnership.

Two companies—Creative Development Partners of Oakland and Orton Development of Emeryville—have been listed as finalists for the bid, with the winner expected to be announced this spring.

Under the terms of the city’s Request For Proposals, the center will be used for both public and private use, with the building façade restored and maintained and the ownership of both building and land remaining with the city but rented out on long-term lease to the developers.

Details of the final development plans will not be released, however, until the developer is chosen.

In its original release announcing the Kaiser project, city officials said that “while proposals should include the restoration of the existing Calvin Simmons Theater, the city is open to creative and new ideas for the adaptive reuse of the rest of the building, including uses such as performance space, entertainment venues, conference and event spaces, light industrial or maker space, commercial office uses and retail and restaurant space.”

Oakland’s decision to restore the Kaiser Convention Center as a public-private partnership may have been inspired, in part, by the City of Richmond’s successful restoration of the old Ford Building on that city’s bay waterfront.

In 2011, the online architectural magazine Archinnovations said of the Ford restoration, “The project converted a crumbling historic icon into a model of urban revitalization and sustainability. [The site] now houses an acre-sized public event venue, restaurant/retail, and tenants including SunPower and Mountain Hardwear. … The restoration and preservation of the Ford Assembly Building … saved an historic architectural icon from the wrecking ball, and converted a long-vacant auto plant into a current-day model of urban revitalization and sustainability.”

Outgoing Oakland Mayor Jean Quan made little mention of the Kaiser Request For Proposals during her unsuccessful re-election bid this fall, concentrating instead on promoting development plans at the old Oakland Army Base, Brooklyn Basin (the old Oak-To-Ninth site south of Jack London Square), and Coliseum City.

And at least one Quan political associate says it is because the idea came from another powerful Oakland government official.

Saying the Kaiser proposal “obviously came from up high,” Oakland architect and housing activist James Vann says that interim Oakland City Administrator Henry Gardner may have been the instigator of the renovation project.

Gardner, who served as Oakland City Manager in the pre-strong mayor days from 1981 through 1983, was brought back by Mayor Quan to serve as interim City Administrator this year after the resignation of Administrator Deanna Santana.

It was widely understood that Gardner had only agreed to serve in that post through the first of next year, regardless of the results of the mayoral election.

“I have a feeling,” Vann says, “that Gardner looked at [several] city-owned properties that are either sitting vacant or the use could be expanded and just decided to go ahead with putting out development proposals for them.”

Vann, who walked door-to-door for Quan during her original bid for mayor in 2010, said that the mayor “never mentioned anything” to him about the Kaiser restoration proposal.

“She’s not opposed to it, but I think she would have mentioned it [if she was behind it.] And I don’t think the new planning director, who hasn’t been here a year yet, would have come up with these plans,” Vann said. “So it seems to me that this is something that would have gone back to Henry and he would have gotten various people to sign off on them. But I have a feeling they originated with him.”

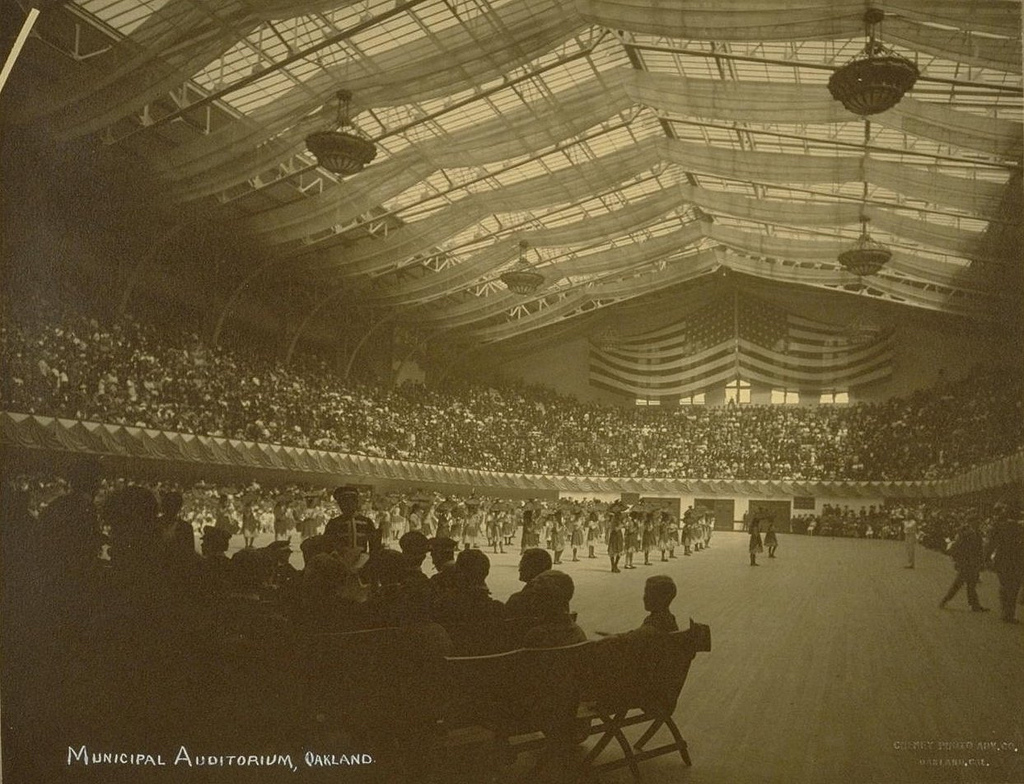

The Kaiser Convention Center sits directly across from where the city has made major public space renovations to the lake and to the adjacent Lake Merritt Channel in the past several years. The Center, which includes an arena and a 1,900 seat theater, once served as Oakland’s major event center, was closed in 2005 for what was called at the time budgetary problems.

That was only three years after Oakland voters passed the $198 million bond Measure DD, and long before the authorized bond money resulted in the complete renovation and restoration of the western end of Lake Merritt and the Lake Merritt Channel, the narrowing of the streetway between the convention center and the lake, and the connecting of the two properties by pedestrian bridges.

When those changes were completed in the summer of 2013, they immediately raised the profile of the Kaiser Convention Center as one of the most important, most visible, and most underused pieces of public property in Oakland.

But long before that happened, and almost as soon as Measure DD passed in 2002, efforts were made within Oakland city government to sell off the Kaiser property, including a little-known behind-the-scenes proposal to tear down the Kaiser and include it in an aborted plan by the state school administrator to turn the nearby Oakland Unified School District Administration Building into high-rise condominiums during the period when the Oakland schools were under state control.

In addition, there was a failed effort in 2006 to pass a bond measure to build a new Main Library on the Kaiser property, as well as a rejection by city officials in 2005 of a joint developer/Peralta Community College District proposal to turn the Kaiser into a performing arts center.

But this new effort is the first time since the Kaiser closed that the property is in line to restore to anything approaching its original position in Oakland public life.

City officials repeatedly failed to answer requests to comment on this story.