Looking for Answers: Why Did Oakland Lose $600,000 for Jobs?

Feb 22, 2013

Posted in Oakland Job Programs

By Ken A. Epstein

Part III

The head of the Oakland Workforce Investment Board has submitted a memo to the City Council blaming the administration of former Mayor Ron Dellums for the loss of over $600,000 in federal funds for unemployed workers, nearly two years after Dellums left office.

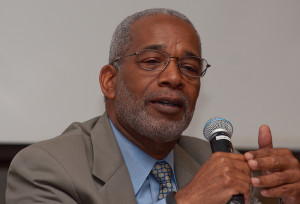

Several problems with carrying out the grant “were not disclosed until October 2011, more than halfway through the funding period,” said John Bailey, executive director of the Oakland Workforce Investment Board in a Feb. 15 memo to Mayor Jean Quan, City Council and City Administrator Deanna Santana.

“When this new administration discovered these problems, staff worked with the California Employment Development Department (EDD), making every effort to correct the contract errors and obtain a three-month extension to the original grant to allow us to expend as much of the grant as possible,” Bailey wrote.

However, according to the state EDD, which was responsible for overseeing the federal money, Oakland had received support and warnings with enough time to spend the money to help the unemployed.

“During the initial phase of this project, the state hosted periodic conference calls with all 20 of this grant’s project operators (grantees). Many of them were challenged to get their projects operational due to their limited expertise running this type of training program,” said Dan Stephens, of the Communications Office, EDD Public Affairs Branch.

“The city was periodically reminded of the need to develop a corrective action plan that would get their project implemented quickly,” Stephens said. “Warnings were issued … primarily through the conference calls … with all the grantees,” he said.

“The city’s current Workforce Investment Act (WIA) administrator John Bailey and his staff were first notified in late October 2011, that the City needed to deobligate (send back) funding from this project or present a written justification substantiating why they should be allowed to retain this funding as the availability of this funding to the state was scheduled to end on June 30, 2012,” Stephens said.

“It’s easy to blame people who are no longer here about why things didn’t work. If you think about the unemployment rate in our city, there should have been some urgency on the part of our administrators,” said Councilmember Desley Brooks.

The Dellums administration applied for and received the National Emergency On-the-Job Training Grant, which was funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act from the Department of Labor in Spring 2010.

Two issues required the new administration to make changes to the original plan. The original plan proposed to train first-time workers, such as the formerly incarcerated, rather than placing laid-off workers in on-the-job training positions, as required by the Department of Labor.

The plan also proposed to utilize Volunteers of America and the Youth Employment Partnership to implement the program, though they had no OJT background or were they part of an open bidding process, as required by the state.

Bailey, who took his city position the beginning of 2011, was previously CEO of Volunteers of America, one of the agencies that had been originally selected by the city to implement the grant.

In part, the WIB staff has said it had no time to find new agencies to implement OJT programs because the Request for Proposal (RFP) progress was too lengthy to complete in the remaining months. But those who are familiar with the procedures say the state accepts other methods of competitive bidding, such as a Request for Quote (RFQ), which could take as few as two weeks.

“They couldn’t get it together to do an RFP. Are you kidding me?” stated Councilmember Brooks.

Initially, $400,000 was sent back on Dec. 27, 2011. An additional $125,462 was sent back on May 7, 2012, Stephens said.

Left in the grant was $200,000, for which the Oakland Private Industry Council (PIC) received a contract from the city three weeks before the originally scheduled sunset date. PIC was able to spend $80,849 by Sept. 30, after the state granted an extension.

An additional $119,150.72 was returned on Nov. 2, 2012 as part of the city’s “closeout,” Stephens said.

In addition, Bailey said WIB has since January 2011 been involved in the complicated process of taking citywide workforce system responsibilities for picking and evaluating agencies to implement programs and to distribute timely funding to these agencies.

“The transition of system administration to the city is nearly accomplished,” he wrote.

“It speaks volumes of the ill preparedness of the (city) staff to take over these functions,” said Brooks. “It has been historically true about the city that we don’t run problems well. The people who suffer are not those who make over $100,000 a year. It’s the people who are supposed to be served by these programs.”

At least one head of a nonprofit who regularly attends WIB meetings warned City Manager Santana in 2011 that the city was facing the loss of federal job funds.

“The WIB has already forfeited some of its funding because they had not produced a plan to the State of California for the use of these funds in a timely manner,” wrote Rashidah Grinage, executive director of PUEBLO in a Nov. 16, 2011 letter to Santana.

“We look forward to an early response which provides an explanation for this irresponsibility and indicates how the problems that exist can be addressed,” wrote Grinage, who never received a response to her letter.

Vice Mayor Larry Reid is planning to hold a public hearing on why the city lost the money and other issues related to the city’s handling of federal job-training fund.