School District Avoids State Takeover with Two-Year $32 Million Budget Cuts

Oct 7, 2017

By Ken Epstein

The Oakland Unified School District’s budget is balanced but fragile, and the consequences of the spending cuts are just beginning to be felt.

The district cut $15.2 million from its budget last school year and adopted a budget this year with $17.3 million in cuts, a total of $32.5 million, according to the district.

Even relatively small over-expenditures could lead to state receivership. That would mean the superintendent would be fired, and the powers of the board would be dissolved, which is what happened in 2003.

During that time, the state-appointed overseer, working with the Fiscal Crisis Management and Assistance Team (FCMAT, which is pronounced fick-mat), dissolved all board committees, including the Budget and Finance Committee, and closed schools without board or public input.

Teacher salary increases were out of the question.

Currently, both the district´s advisory state trustee and FCMAT representatives have spoken to the board, using virtually the same words, “If you can’t make the cuts, the state will come in and make them for you.”

Only a little over a month into the school year, schools are feeling the impact. The district is “consolidating” or involuntarily transferring teachers from schools where student enrollment is less than what was projected to other schools that need additional teachers.

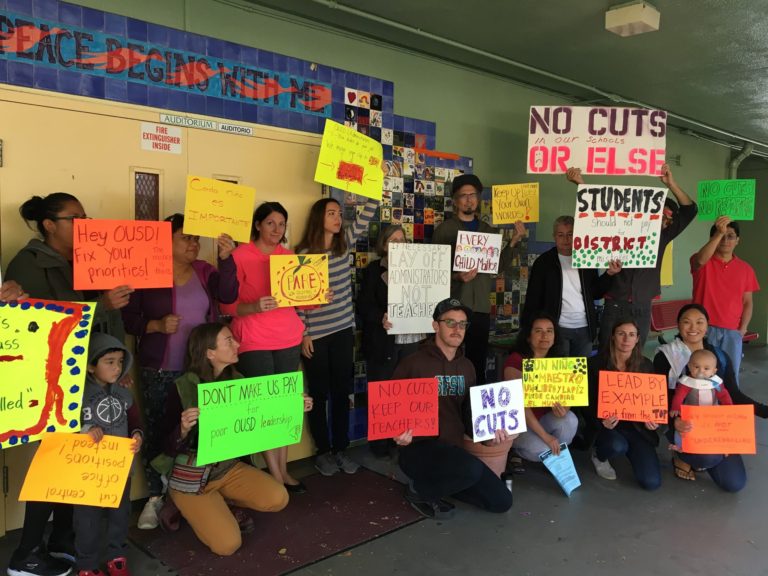

The board and administration are facing protests, including at Manzanita Community School, an elementary school at 25th Avenue and E. 27th Street. Parents, staff and students are angry over the loss of their teachers and the disruption of their schools.

In addition, the district is under strong state pressure to close schools, similar to what happened in 2003. Board members are expected to consider school closures in coming months, to be potentially implemented as soon as next school year.

While FCMAT representatives tell the board they will be “amazed” how much money OUSD saves by closing schools, a number of national reports indicate that shutting schools does not produce the desired cost savings and also damages the education of students at both the schools that are closed and those that receive the transferred students.

In California, state law requires the district to turn over its closed to schools to charter school organizations if they want them. As a result, schools that are closed one year could reopen as charters the following year, possibly enrolling a number of the students from the public schools that closed.

According to activists, under these conditions, school closings would in effect be a transfer of public property to privately run charter organizations and decline in the numbers of students – not a road to renewed financial health but to permanent damage to public education in Oakland.

The board only recently re-instituted the Budget and Finance Committee that had been dissolved under state receivership.

Though the challenges are daunting, community members and OUSD staff are heartened by the school board’s decision to hire Superintendent Kyla Johnson-Trammell, an Oakland native who has nearly two decades of experience, believes in Oakland and its schools and has a track record of transparent decision making and respectful relations with the community.