West Oakland Residents Not Receiving Army Base Jobs

Aug 15, 2014

Posted in Army Base Jobs, Business, Community, Economic Development, Equal Rights/Equity, Labor, Oakland Job Programs, Transportation

By Ken Epstein

The Oakland Post has received replies from Master Developer Phil Tagami and the City of Oakland providing some of the numbers detailing the construction jobs Oakland residents have obtained so far at the $1.2-billon Oakland Global Army Base project.

To date, the project has produced jobs for 425 workers, who have worked a total of 95,515 hours. Of these, 14,264 hours went to African Americans, according to data supplied by the city.

In other words, while African Americans represent 27.3 percent of the city’s population, they have received 14.9 percent of the total work – underrepresented by 45 percent.

nly 3,503 hours or 3.7 percent of the total hours went to workers who live in West Oakland, the community next to the Army Base that is directly impacted by Port of Oakland truck and maritime traffic.

According to another city report, 171 new hires were put to work between Oct. 1, 2013 and Aug. 1, 2014. Of these, 98 or 57 percent were Oakland residents, though 25 of these were apprentices, who are near the bottom of the pay scale.

Workers in West Oakland, zip code 94607, were hired in eight of the Oakland positions, including four who were apprentices.

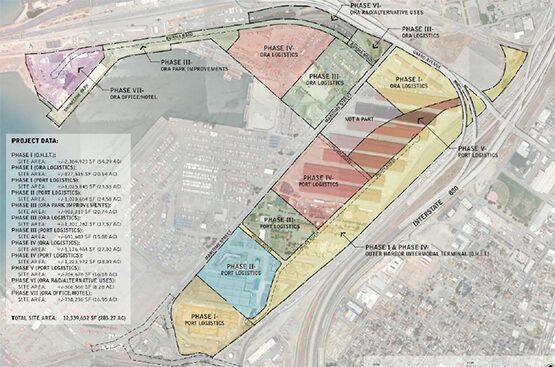

Tagami, who is both the primary developer and the agent hired by the city to oversee the project, has said the Army Base is in the initial five-year phase of the development, which will take 20 years to complete.

Concerned about what many are saying are unsatisfactory numbers of new jobs, community members are asking about what results have been produced by the West Oakland Job Resource Center, which has sent only 11 workers to the Army Base through June.

The job center was funded by the City Council at about $500,000 a year to serve as a jobs pipeline and clearing house for the project. It was designed as a watchdog over all the new jobs to avoid the broken promises of the past, to ensure a place at the table for Oakland residents who want to break into good construction jobs.

But somehow, either in the way the agreement was ultimately written or by staff interpretation, the job center has turned into something else.

Deborah Barnes, manager of the city’s Department of Contracts and Compliance, explained that contractors and unions are allowed to bypass the jobs center to send people to the Army Base.

“There is no provision in the Community Jobs Agreement or the Project Labor Agreement that designates the Job Resource Center as a ‘clearinghouse’ for all jobs on the Oakland Army Base Project,” said Barnes, describing how the city is implementing the center.

“The unions do not inform the Job center of every new hire they send to the project. There is no provision in the (agreements) that requires the unions to provide this information to the center,” she said, adding that the information can be taken from reports contractors submit to the city.

However, when the proposal for the job center was approved by councilmembers, they were told that it would be a “clearinghouse” for jobs at the Army Base, said Lynette McElhaney, whose district includes West Oakland and the Army Base.

“It is supposed to be a clearing house, to do outreach and provide resources – a place where employers can find workers and that will support job seekers,” she said.

McElhaney she had been told by staff that the job center has only sent 11 workers to the Army Base. “They tell you how many hours people have worked, but not how many people are represented by those hours, how many people are from West Oakland,” she said.

Brian Beveridge, a leader of the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project and OaklandWorks, sat at the table and was part of the negotiations that produced the agreement to create the job center.

“We tried to create a system that doesn’t punish the people who have always had the jobs (in the past) but would help the workers who have not been part of the process,” he said.

If a contractor needed a worker, he could call the job center or the union, which would notify the job center. “There was supposed to be to be a simultaneous call to both the job center and the union,” he said.

The job center would maintain a central database of workers, their skills and training needs that employers could draw upon and would provide transparent proof of whether the city and developers were “delivering on their promises or not,” said Beveridge.

But now, he said, “We essentially have the same system that we had before the Job Center. They’re still not putting people in West Oakland to work.”

Like in the past, the system is “failing the people in West Oakland who really need to work,” Beveridge said.