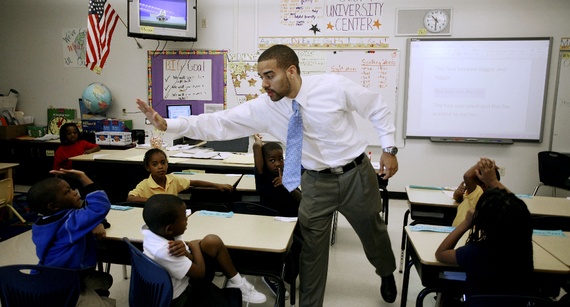

Systemic Barriers Keep Teachers of Color Out of Oakland Classrooms

Aug 30, 2014

Posted in Education/Schools/Youth

By Ashley Chambers

There are no shortage of reports that point to the lack of diversity among urban teachers, but most of these reports fail to pinpoint and find solutions to the obstacles that keep potential teachers of color – particularly African Americans and Latinos – from going to work in elementary and secondary classrooms.

“There’s a whole set of barriers that have been erected over the past 20 years that keep people out of teaching,” said Kitty Kelly Epstein, who teaches at Holy Names University in Oakland. “There are multiple standardized tests that exclude people of different groups, costs of these tests, and some programs require you to teach for a year for free.”

As a result many students go through school without hardly ever having a teacher who looks like them and might share similar cultural experiences.

A recent report by the Center for American Progress underlined the lack of teacher diversity in public schools across the nation. The report finds that the teacher diversity gap is growing in nearly every state. More and more, students of color in urban schools are now being taught by White teachers.

The Oakland Unified School District, which for a variety of reasons has representation that is better than national and regional averages, is still failing to recruit a teaching force that does not come close to representing the students who attend public schools in the city.

Of the 46,486 students who attended Oakland schools in 2012-2013, the student body was 9 percent white, 29 percent African American, 42 percent Hispanic/Latino and 15 percent combined Asian, Pacific Island and Filipino.

By contrast the district’s staff of 2,562 teachers were overwhelmingly white – 45 percent. Eighteen percent of the teachers were African American, underrepresented by 38 percent in comparison with the numbers of Black students in the schools.

Ten percent of the teachers were Latino/Hispanic – 75 percent underrepresented in comparison with the student body. Asian, Pacific Islander and Filipinos made up 13 percent of the teachers – 13 percent underrepresented.

The basic requirements to become a teacher include completing a bachelor’s degree, taking the necessary test assessments such as the California Basic Educational Skills Test (CBEST) and the California Subject Examination Test (CSET), and completing a credential program, many of which require one year of free practice teaching.

Although the requirements to enter teaching should be rigorous, says Dr. Epstein, incoming teachers should be assessed on “the reality of their knowledge, their commitment and their ability to engage the students” – not just paper and pencil tests.

“Because of the racial wealth gap, the extra costs and unpaid labor fall more heavily on those from communities with less wealth. Every new requirement is an extra cost, and every extra cost means the loss of thousands of potentially effective teachers,” Epstein added.

“The disparity of a lack of racial and cultural diversity is a national issue – it’s not just Oakland,” said Jumoke Hinton Hodge, District 3 Oakland School Board member.

Hodge, who has served on the school board since 2008, says she finds many obstacles that limit access to teaching for people of color.

“I think that as a district, we have to identify those barriers and figure out how Human Resources is going to support [incoming teachers]. We have to look at how we retain people and make sure that there’s opportunity for growth inside our system,” she said.

Oakland has begun to come to grips with the lack of teacher diversity through Teach Tomorrow in Oakland (TTO), a program that was started as a partnership between former Mayor of Oakland Ron Dellums and the school district to recruit local teachers that reflect the diversity of Oakland students.

Seeking to overcome the revolving door of teachers who come and go in urban classrooms, TTO requires teachers to commit to five years working in the city’s highest need schools and provides them with the resources they need to be successful – in-class coaching, monthly professional development sessions and free tutoring support to help pass the standardized tests required of all new teachers.

“For Oakland, and even nationally, until recently districts have contracted with national recruiting agencies, and the people recruited haven’t looked like the people in the community,” said Kimberly Mayfield-Lynch, chair of the Education Department at Holy Names University.

Sixth grade teacher Francisco Ortiz says that he finds that Latino and other educators may not want to teach in urban schools because the pay is low and classrooms lack supplies and other resources.

“There is a lack of resources afforded to most neighborhoods that serve children of multi-cultures or lower socioeconomic status,” he said.

At bottom, the problem comes down to a lack of compensation and incentives to hire young people to go into teaching and provide a better working environment so that they will stay in the profession, said City Councilmember Noel Gallo, who served on the school board for 20 years.

“To be a teacher takes a true commitment to helping people, and the compensation may not be the greatest,” which is true locally and at the state and national levels, Gallo said.

Some people are wary of going into teaching because of all the negative reporting they hear about public schools and educators, said Mayfield-Lynch.

“For years, teachers were the bedrock of the community,” she said, but now the profession is taking a beating.

“At the end of the day, what is really clear about the profession is that it’s always going to be there, and the beginning salary for a lot of people is the first step to a middle class socioeconomic status,” she said.