Oakland Teachers take on The State

Mar 2, 2019

Standing behind the scenes of the battle between Oakland’s school district and its 3,000 teachers are State representatives controlling the district and enforcing drastic budget cuts.

By Ken Epstein

The officials who control the Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) on behalf of the State of California mostly operate behind the scenes, meeting in private with school board members and district staff.

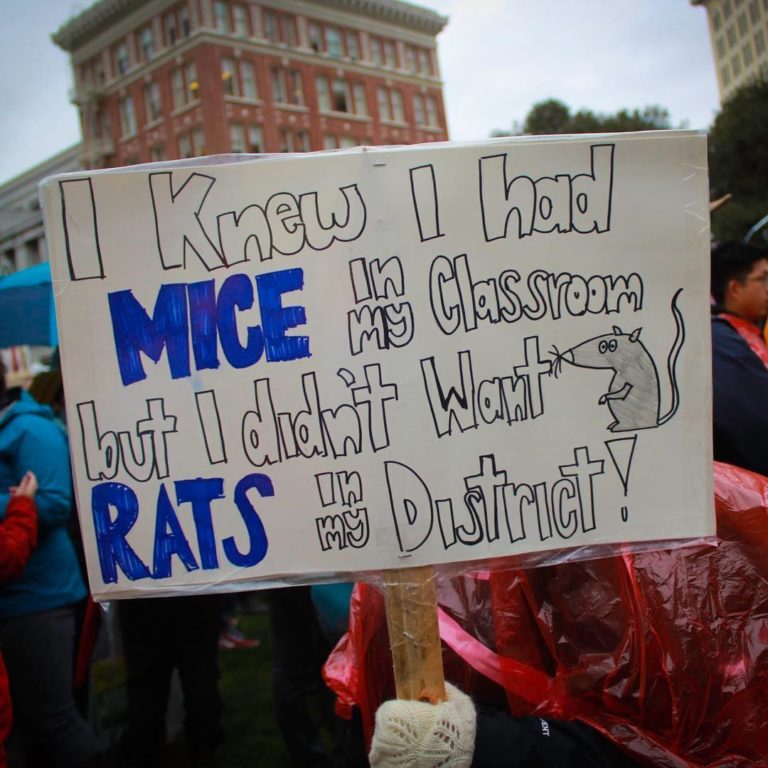

But this week, the overseers came out publicly in defense of the state’s austerity program for OUSD, as they sought to counter the enormous resistance of striking Oakland teachers, backed by the solid support of students, parents, community, churches and city leaders, fighting for higher teacher salaries, more counselors and nurses, smaller class sizes and a halt to school closures.

“Under my authority as the Fiscal Oversight Trustee for OUSD, I will stay and/or rescind any agreement that would put the District in financial distress. A 12 percent salary increase would do just that. What the District has on the table now is what the District can afford,” said (State) Fiscal Oversight Trustee Chris Learned in a press statement released by OUSD last Sunday.

Where did the trustee come from, and where did he get the authority to say what he said?

A little history: while OUSD was under receivership (2003-2009), the district was not allowed to hire a superintendent, and the power of the board was suspended. The district did eventually hire a superintendent, and restore the school board. However, what came next was not local control, but modified state control.

“(Since 2008), OUSD began operating with two governing boards responsible for policy—the state Department of Education and the locally elected Oakland Board of Education,” according to the district’s website. A state trustee was appointed with power to nullify district financial decisions.

Rather than serving as an independent outside evaluator, the state forced a $100 million bailout loan on the district in 2003 and spent the money with no local input—a debt which costs OUSD $6 million a year until 2026. The state was in control while a spending spree during the administration of pro-privatization Supt. Antwan Wilson almost bankrupted the district.

The reality of the state’s current authority over Oakland schools, going back to 2003, was presented last October during a rare joint public appearance at a school board meeting of the officials who are in charge of Oakland schools: California Deputy Superintendent of Public Instruction Nick Schweizer, Trustee Chris Learned, Fiscal Crisis Management and Assistance Team (FCMAT) CEO Michael Fine, and Alameda County Superintendent of Schools Karen Monroe.

The officials came to Oakland to explain the meaning of AB 1840, a new law backed by then Gov. Jerry Brown that would give more power to FCMAT (pronounced FICK-MAT) and Alameda County. They spoke about collaboration and teamwork, while demanding Oakland close schools and cut $30 million from its operating budget.

FCMAT is an independent nonprofit based in Bakersfield, funded by the State and representing the State’s authority in districts throughout California. FCMAT was directly involved in the passage of AB 1840.

Speaking bluntly, FCMAT CEO Fine said the district has no choice but to make budget cuts and close schools.

“If you failed at this, the county superintendent would come in and govern the district,” Fine said. ”The county supt. already has the authority that, if you don’t do what’s right, to impose a functioning budget on you.”

“We do this every day, guide districts through this every day. It is ultimately less painful to make your decisions as early as possible,” he said. “Cutting three dollars today rather than a dollar today, a dollar tomorrow and a dollar (later)…allows the district to get to its new norm much quicker.”

Fine said that the school district has “struggled for many years” to close schools, based on a formula for the appropriate number of students for the square footage of classroom space.

“That is one of the specific conditions in 1840,” he said. “1840 says that we are going to partner with you so that you can implement these plans in a timely fashion and buy a little bit of time, and it is just a little bit of time, so you can incorporate good decisions.”

While saying the district’s sole responsibility is to “close the gap” and end its “deficit,” Fine admitted closing schools does not save money. “When everything is said and done, the actual dollar savings are relatively small—you don’t see the savings,” he said.

Fine said that over the course of 27 years, he has had a lot of experience closing schools. “I’ve had to close some….lease some…sell some and exchange some for other properties. It’s a long and difficult process,” he said.

He also emphasized the importance of the budget cuts. “You’ve made a very public commitment to a set of reductions that total about $30 million….If you stop at $15 million, you do not achieve the benchmark…It is your job to figure out the details.”

County Supt. of Schools Monroe explained that under the implementation of AB 1840, she is working closely with FCMAT. Trustee Chris Learned now reports to her office, rather than the state.

Calling the budget cuts a team effort with the district, she explained that her office—the Alameda County Office of Education—and FCMAT will “confer and agree on the operating deficit and the next steps that are part of the legislation.

“If we see that those budget balancing strategies are not being implemented, then we will have to impose strategies,” she said.

In the midst of the ongoing Oakland teachers strike, following on the heels of the successful strike of Los Angeles teachers, new opportunities are now opening up to change the state’s long-term policies of underfunding public education and enforcing austerity on individual school districts.

One sign of that movement occurred Monday when State Supt. of Instruction Tony Thurmond intervened in the Oakland strike, joining teachers and district representatives at the bargaining table in an attempt to close the deep divisions between the parties.

Further, as community awareness grows about the role of the state in this strike, many are looking to the local state legislative delegation—Senator Nancy Skinner and Assemblymembers Rob Bonta and Buffy Wicks—to muster support in Sacramento for a more positive direction, one that embraces the needs of Oakland teachers, students and community.