Environmental Groups’ Legal Action Could Halt Coal Terminal

Oct 28, 2015

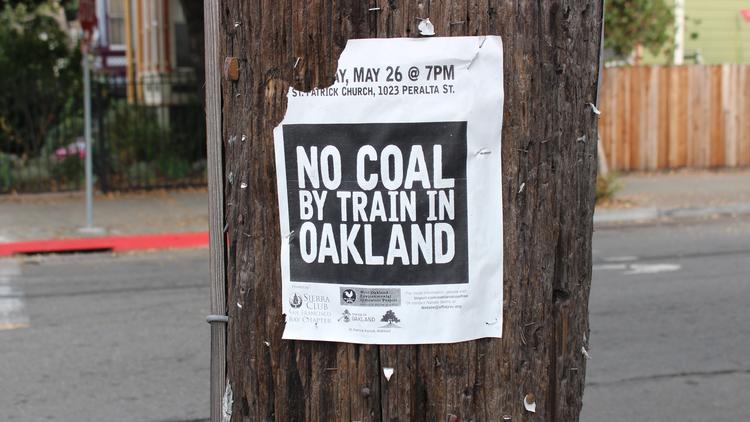

Sierra Club poster in West Oakland. Photo courtesy of SF Business Times.

By Tulio Ospina

Environmental and community groups – Earthjustice, the Sierra Club, Communities for a Better Environment (CBE) and San Francisco Baykeepers – have filed a California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) action in Alameda County Superior Court challenging the export of coal being through Oakland.

According to Earthjustice, which filed the claim on behalf of the other groups, the original CEQA review of city’s Army Base development, performed over a decade ago, “failed to include any discussion or analysis of the impacts of transporting, handling, or exporting coal from Oakland on surrounding neighborhoods or the environment.”

It was not until April 2015 that the public learned that the bulk terminal’s developer, Terminal Logistics Solutions (TLS), had plans to use the Oakland Bulk and Oversized Terminal (OBOT), to export coal coming from Utah.

Prior to this revelation, Phil Tagami, owner of California Capital & Investment Group (CCIG), with whom the city had signed an agreement to build the terminal, had publically promised that coal was not an option as an export commodity.

After public outcry this year, the City Council has agree to study whether the export of coal through Oakland poses “health and safety” hazards to adjacent communities and those working at the terminal.

A clause in original development agreement between Tagami and the city allows the Oakland to halt shipments of a commodity on the property if those shipments would place workers and adjacent communities “in a condition substantially dangerous to their health and safety.”

The environmental groups’ CEQA challenge give anti-coal activists significant bargaining power, since the entire Army Base develop could be halted for up to two years if the groups decide to call for an injunction.

The environmentalists say they do not want to halt a project that is overall good for Oakland but may be forced to do it the city fails to regulate or mitigate the impact of transporting coal through Oakland.

“Our goal in this process is to make sure the public really truly knows what will happen if a coal terminal goes up in their backyards and that the city complies with their desires,” said Irene Gutierrez, an attorney at Earthjustice’s California regional office.

“Our goal in this process is to make sure the public really truly knows what will happen if a coal terminal goes up in their backyards and that the city complies with their desires,” said Irene Gutierrez, an attorney at Earthjustice’s California regional office.

“There was not an environmental review for a project like this (involving coal), and new information has come up, and CEQA allows you to sue if that is the case,” she said.

Meanwhile, the environmental and community organizations have written a letter to the California Transportation Commission (CTC) opposing what they see as a misuse of the public grant that was used to fund half of the project.

They have requested that the CTC provide an extension to the grant’s deadline, which will allow the project to find required matching funding to replace the money the project is hoping to receive from Utah.

The bulk terminal project was funded by $242 million from a voter-approved Proposition 1B Trade Corridor Improvement Funds, which allocated $20 billion in bonds to “advance infrastructure projects and air quality improvements throughout the state,” according to the letter.

CTC funding supports “projects that improve trade corridor mobility while reducing emissions of diesel particulate and other pollutant emissions,” according to Prop. 1B.

“The $242 million from Prop 1B is meant to protect communities from further being polluted and impacted from these industries,” said Jess Dervin-Ackerman of the Sierra Club’s San Francisco Bay Chapter.

“The fact that the money is being used to build a coal export terminal flies in the face of (the proposition’s) intentions and is not the right use of that public fund that would make the Port of Oakland host dirtier operations,” she said.

Because $53 million in matching funds for the OBOT would be coming from parts of Utah where the coal is mined, developers claim that regulating or prohibiting coal—or filing an injunction through CEQA—would leave the development stranded without necessary matching funds, thus shutting down the entire project.

To avoid a shutoff the environmental groups have asked for the extension on the deadline for securing matching funds.

“It’s important to affirm that the groups that are participants in the (CEQA) lawsuit are supportive of job creation and economic revitalization in Oakland,” said Gutierrez of Earthjustice. “But they want to make sure the city is informed and takes the measures it can to protect the public and keep the public

informed.”

While the City Council has until Dec. 8 to make a final vote on its regulatory options surrounding coal, a number of people are challenging whether the city has the authority to regulate commodities that are being transported on federal railways.

“If this city were to take a position that coal could not be transported in interstate commerce, that would be a problem and would be (federally) preempted,” said Kathryn Floyd, a lawyer for Tagami’s company, CCIG, speaking at a Sept. 21public hearing.

Disagreeing, Gutierrez says the council does have the power to regulate commodities on city-owned property.

Seeking clarification of the city’s rights, the Post has asked City Attorney Barbara Parker, an elected public official, whether “a simple majority (is) needed in the City Council to determine whether or not the export of coal would constitute a health and safety danger to Oakland residents?”

Parker’s office responded that she “can’t disclose legal advice. Any advice or opinions we provide to clients is privileged and confidential, and in fact we can’t disclose whether or not we have provided advice on any given issue. We can disclose only if the Council waives its privilege.”