A Push for Alameda County to Fund Reentry Programs

Mar 15, 2015

Posted in Economic Development, Equal Rights/Equity, Health, Oakland Job Programs, Police-Public Safety, Reentry/Formerly Incarcerated

By Ashley Chambers

A number of local groups are challenging how Allemda County is spending the millions of dollars a year it has begun receiving to partially offset the state decision to save money by shifting many inmates from state prisons to local jails.

The Urban Strategies Council and a number of other organizations, including the Ella Baker Center through its Jobs Not Jails campaign, disagree with how the funds are divvied up, saying not enough public safety funds in Alameda County go to support individuals reentering society from prison.

The Jobs Not Jails campaign is asking that half of the $34 million a year, or $17 million, go to reentry services.

In a letter to the Alameda County Board of Supervisors, the Ella Baker Center cited statistics that show that a shift in how these funds are invested could reduce recidivism and produce savings for the county.

Over half of the county’s budget – in excess of 60 percent – currently goes to the sheriff’s and probation department.

The Ella Baker letter also cites statistics that show a decline in the total number of felony arrests in Oakland by nearly 28 percent since 2011 when Assembly Bill 109 was passed to reduce the number of inmates in state prisons.

Prop. 47 was passed last year reducing penalties for some nonviolent crimes from a felony to a misdemeanor and has resulted in further decline in the jail population.

Local organizers say now is the best time for the Board of Supervisors to start shifting how they are spending the money.

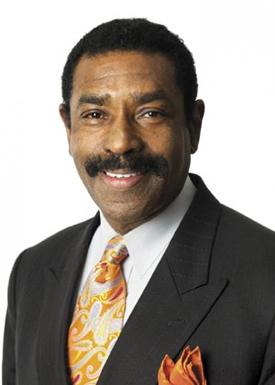

“The way we’ve operated our system hasn’t worked,” said Junious Williams, CEO of The Urban Strategies Council, pointing to a continuing high recidivism rate in Alameda County.

“There’s too much investment on incarceration, parole, and probation, and it’s not very effective,” he said.

“There is an imbalance in our investments, and that is not very constructive for our society,” Williams added, noting that funds are directed toward enforcement and incarceration rather than reentry programs and supportive services.

Nearly 27 percent of the county’s 2013-14 public safety budget went towards reentry programs.

“What would it mean to invest in more programs and services to help people on probation and that are coming out of prison to be successful?” Asked Williams.

Investing half or more of funds to job training, housing, and wraparound services for the reentry community would not only reduce the number of people going back to jail for a crime committed after their release, but also contribute to safe and strong communities, say organizers.

The Ella Baker letter says: “Jail beds cost nearly $50,000 a year while providing an ‘On the Job Training’ (OJT) employment opportunity costs $4,000 and can provide paid job experience that can lead to a long-term position.”

Supervisor Keith Carson is supporting a proposal to begin directing the funds – $17 million – to community-based organizations that work with the reentry population beginning July 1, 2015.

“I think it’s very important that we have community funds,” said Supervisor Carson, “and that 50 percent are spent on reentry programs that are community-based, that are diversified and that work.”

The county recently formed a Community Advisory Board, made up of community members from all five districts who work with the formerly incarcerated.

This board will guide the process of how community-based groups are chosen to receive funds for their work to support reentry individuals.

“There are very few community-based groups providing mental health services, drug and alcohol treatment, workforce development,” and other services, Carson said.

“This is really about independent programs that are community-based, since there hasn’t been monies going into that direction, to provide those services for the purposes of serving everybody, including the reentry population,” he said.

He continued, “Now, locally we have an open democratic process to try to figure out how to have the best impact for the reentry population.”